By Debbie Black and guest, David Black

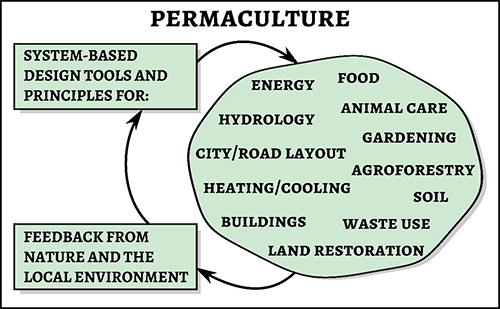

A permaculture diagram. Image by David Black

The word permaculture keeps popping up lately. What the heck is it? Does it have to do with soil? Water? Vegetation? Animals? Wind? Sun?

I found complex definitions that boiled down to this: A problem-solving design approach that increases profitability and productivity of food, fuel and fiber by observing and mimicking nature, while no longer ignoring ecosystem health.

That sounded like an indisputably good thing, but still vague. I wanted to know more. What does permaculture encompass? How’s it implemented? Is it big picture thinking, or can the principles be applied to my tiny yard in Cayucos? Too many questions. I had to call in the big guns—my son, David, who has studied permaculture for a number of years and is certified in permaculture design. Here is David’s perspective on permaculture, and how it can be implemented in our local gardens:

At the very core of the principles of permaculture is a desire to have a society that can endure far into the future. The term itself, coined by Mollison and Holmgren, is a portmanteau of the words “permanent” and “agriculture” and that is still a primary focus. Over time, however, it has also gathered tools to apply this philosophy of endurance to many other aspects of modern society. When looking at the diagram, it might be tempting to think: “Oh, so it’s just referring to design of anything?” Well… sort of. To pull back from this level of abstraction, let’s look at a common problem and apply the permaculture lens:

Imagine you have a dirt road on a hill that needs resurfacing every year due to rutting caused by rainstorms. One approach to dealing with this is to keep resurfacing it or just tolerate a terrible surface and drive over it very slowly and carefully. This might be called the “there is no problem” mentality.

A second solution would be to grade the road with a 5% cross-slope and cut a drainage ditch alongside that sends the water out to a storm drain as directly as possible, preventing erosion of the road surface. This mentality could be called “the problem is a problem” and represents the most frequent design approach taken today, particularly in large projects with narrow goals like keeping the road accessible at all times.

Now, a permaculture designer would look at this and just be bubbling with excitement; free water high up on a property that is already concentrated on a road! Their design would probably include the same 5% cross-slope to the road surface and the same drainage ditch, solving the issue at hand. However, they might then route the water out into three on-contour soakage trenches, or swales, and plant a dozen fruit or olive trees along each one. The water is now kept on the property in a passive, low-maintenance system that grows some extra food or a minor cash crop for the landowner. The land itself also becomes healthier and more productive over time because of this small addition to the design. Permaculturists refer to this last mindset as: “the problem is the solution,” implying that most hurdles in a design can be solved in a way that also provides an ancillary benefit when looked at with the appropriate lens.

In our area, the problem of poor soil and the problem of kitchen food waste dovetail into a ready-made solution to grow healthier plants. All soils benefit from some good, natural compost. A simple composter is an easy, rewarding way to turn kitchen greens and yard clippings into free rich mulch for your vegetables, herbs, trees or house plants. An inexpensive composter (like Algreen Soil Saver from Home Depot or unclejimswormfarm.com) can also become a worm bin by adding worms. This is a good family project for kids to learn permaculture in a fun way. Got extra kitchen and yard waste? Find a neighbor with chickens and offer to augment their feed—another example of permaculture’s no waste/closed-loop systems. You’ll get to know your neighbor, and might even score some eggs.

After you have healthy soil, you’ll need to choose plants for your design. Most plants on permaculture lists provide something edible (leaves, shoots, roots, fruits, etc.) but others can pull nitrogen from the air, provide shade, wind or erosion protection, or be nutrient accumulators. Planting two or more mutually beneficial plants next to each other is another example of permaculture—called companion planting. Companion plants are shrubs, herbs, fruits, and vegetables that provide their neighbors with something: nutrients, a climbing structure, shade, or protection from disease and pests. For a list of companion plants, go to trees.org/post/companion-planting-101/ or for a list of permaculture plants, check out tobyhemenway.com or pfaf.org.

Don’t have a yard? Morro Bay and Los Osos have community gardens, or you can offer to plant a neighbor’s yard and share the bounty. For more permaculture info and new “permie” friends, go to https://slopermaculture.weebly.com/.

Debbie Black is a member of The BookShelf Writers. To see more of her work, please visit thebookshelfwriters.com. Contact David Black at DesignAFuture@protonmail.com