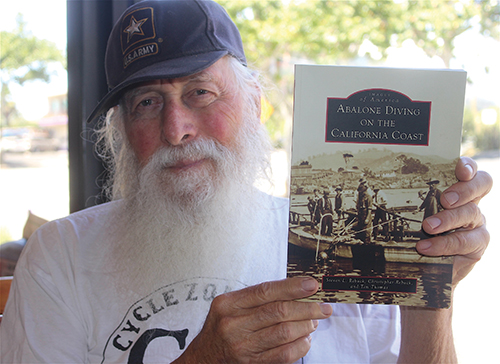

Steve Rebuck just released a book through Arcadia Publishing entitled, ‘Abalone Diving on the Central Coast,’ a history of the industry told mainly through historic photos.

A new book by a local man explores the rich history and fascination man has had with the sea, in particular the sea snail, abalone, and its influence on the Central Coast from ancient times to more recent history and through various stages of innovation in the exploration of the ocean.

Steve Rebuck, who lives in San Luis Obispo and spent pretty much his whole life working in and around the abalone fishery and has been an advocate and expert, just released a book through Arcadia Publishing entitled, “Abalone Diving on the Central Coast,” a history of the industry told mainly through historic photos.

Rebuck put the book together with help from his oldest son, Christopher, and Tim Thomas, a writer who wrote chronicled the abalone industry focused on Monterey and Pop Ernest, a restrauntuer and diver who first cut abalone into steaks for a restaurant he owned.

Thomas, Rebuck says, contributed a whole section of his book telling the fishery’s story in Monterey. Christopher, and Morro Bay resident Janice House, did technical work for the book. “We repackaged the photos into modern materials,” he explains.

By that he means taking delicate old photographs and scanning them into digital files and prepping them for publication and to preserve the images for posterity. Arcadia wanted at least 200 photos for the book, he says.

That’s something Rebuck, who has been dealing with health issues for a couple of years now, says is important because it helps tell the remarkable story of these diving pioneers, who over the years invented and developed the equipment — from dive boats, to dive suits and other equipment that’s allowed mankind to reach into the sea and harvest its bounty.

Like others of Arcadia’s thousands of books, this one focuses on localized history using many photos taken by one of the early pioneers of the genre.

“Glen Bickford,” Rebuck says, “a lot of the images came from Glen.”

Bickford, he explains, worked as a hardhat diver and pioneered underwater photography and filmed documentary style footage of the men he worked for and with. He and Rebuck were friends.

“I visited him regularly at his house on Monterey Street [in Morro Bay], that was across the street from the Paladini Building.”

The Paladini Building was a tiny wooden shack really that at one time was a busy processing facility in town, turning the abalone harvested in local waters into what for decades was a delicacy and regular menu item in California restaurants and beyond. It was one of numerous such processors in Morro Bay, as Rebuck recounts some of the others that used to be on the Embarcadero but are long gone now.

Abalone processing was being done at what is now Tognazzini’s Dockside, where Don and Chuck Sites did abalone, and then Mrs. Krill got into it, he says.

The Ocean House was where the old Coffee Pot Restaurant and now Giovanni’s, was located. A dirt lot (now paved) fronting the street was where abalone divers worked on their boats.

Neil McCutcheon had a plant, and then there was one at what is now the Boatyard Center, Rebuck continues, and then there was a guy named Wilson. “Bob Wilbur of Bob’s Seafood, he was a diver, too.”

Up on Beach Street was Betty Jameson’s processing plant. “Along the waterfront there were six to eight processing facilities,” he says. This was from the 1920s to the early 1960s, when the whole thing started to slow and ultimately crash in the mid-1970s.

“Abalone built Morro Bay,” Rebuck says. “Abalone fishing was consistent for decades.”

When the late Joe Giannini arrived, he brought shark fishing to town, Rebuck says. The fishing industry has concentrated on different fisheries since that time, with each one having a heyday before being restricted mainly through government regulations.

That Paladini Building too has since been torn down and housing built. The front façade was saved and is stored at the Maritime Museum.

“After Glen died,” Rebuck says, “his niece, Genie Kitzman, gave me some photo albums.” Bickford was already living in Morro Bay and started shooting photos of the abalone divers in the 1940s and early ‘50s. He built watertight camera casings to be able to shoot first photos and then do films underwater. He also worked on a groundbreaking study of abalone from Catalina to Northern California.

Rebuck’s roots sink deep into the industry. He mentions Al Hansen and his wife. “My dad worked for him when I was born,” Rebuck says. “He ran the boats.” During World War II, Rebuck’s dad built Liberty Ships and was planning to buy a boat and start diving for abalone, which was a pretty lucrative fishery at the time. He moved up to Morro Bay in the mid-1950s.

“The day I was born,” Rebuck says, “my dad went abalone diving, and then bow hunting [where he shot a wild goat] and then he came to the hospital to see me and my mom.”

He laughs that the first scents he ever smelled were his mother, his father, abalone and goat. “I was born into it,” he says. He even includes a photo of his dad’s boat flying some unusual white flags. “There’s a photo of my dad’s boat with my diapers flying over it.”

In the early days, before they moved offshore, abalone divers used to gear up and wade out from the beach. “Can you imagine,” Rebuck says, “they walked through the surf with 150-pounds of equipment on? Then they carried out 50-60-pound sacks of abalone.”

He talks about someone named, Barney Clancy, who ran a fleet of war surplus boats, dubbed the Black Fleet. That’s because back then military boats were painted black with red trim.

He had five boats operating, Rebuck says of the Black Fleet. “Each had a quote of 200 dozen abalone a week.”

He says someone once asked Clancy why he put that quota on his captains. “He said it was because that’s all he could process. That was how healthy the resource was at the time.”

He says the record haul was 168 dozen abalones in a single day, which was accomplished by Walter “Duke” Pierce, whose locally-famous family started abalone diving in Morro Bay in the late 1920s.

“All the abalones were 8-inches,” Rebuck says. “That was the legal size.” He says that over the years he dug through the many shell piles that used to be all around Morro Bay and never once found an undersized abalone, or “shorts,” as they are called.

“They were so plentiful,” he says, “they didn’t have to cheat.” Duke Pierce had a belt that declared himself “The World Champion Abalone Diver,” Rebuck laughs.

He cites statistics compiled by the California Department of Fish & Game (now Fish & Wildlife), published in an agency bulletin from the abalone heyday. “In 1962,” Rebuck says, “Morro Bay had landed 2 million pounds of abalones.”

That was from 1916 to the early 60s. But by 1976, it had all collapsed and Rebuck knows why.

“What changed was the arrival of the sea otters. That put my dad out of business.”

Over the years, Rebuck has been an outspoken critic of the government’s handling of the southern sea otters. That’s including the Channel Islands, San Nicholas Island in particular, where in 1979 the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service relocated otters, with only a handful surviving the move. The sea otters were relocated only to see the lobster, sea urchin and abalone stocks plummet at San Nicholas. “Some of us here knew what was going to happen,” Rebuck says.

But he stresses that all that political history with sea otters and the government’s relocation schemes that he says failed, is only briefly mentioned in the book.

“I only briefly touch on that,” he explains. “I didn’t want to dwell on it. I left most of that stuff out. I wanted the book to be about the people.”

The book is split into three main sections. The first section talks about Native Americans in the area, who first harvested abalone thousands of years ago and made “money” out of abalone shells.

The Spanish, who were the first Europeans to conquer California weren’t fond of the mollusk. “The Spanish thought they were poisonous,” Rebuck says. “That’s from paralytic shellfish poisoning. So the Spanish didn’t fish abalone.”

In 1850, Chinese laborers started coming here to work in the gold mines and on the railroads, Rebuck says. In China abalone were a delicacy eaten mainly by royalty and not common people. “A lot of them ended up in Monterey,” he says of the Chinese immigrants. Seeing the abundant shellfish a fishery naturally sprang up, with the abalone being sent to Asia. “The Chinese took over.”

The government started putting restrictions on in the early 20th Century, including banning the harvesting of abalone in less than 20-feet of water, which targeted the Chinese free divers.

The Japanese arrived around 1896, Rebuck says, and started using heavy diving equipment and diving deeper. The Japanese were primarily working north of Pt. Lobos. “It was better fishing up there,” Rebuck says.

The second section of the book discusses abalone’s role in Monterey’s rich fishing history. The third section, by Rebuck, talks about Morro Bay and the Pierce Family that started the fishery here in 1928.

He also talks about the rich history of technological innovations in diving that arose out of the abalone fishery, including the use of mixed gas to allow humans to dive deeper and combat the bends.

“In 1962,” he explains, “a fellow by the name of Bob Kirby, who started building dive helmets in Morro Bay, was the first to dive to 400 feet in Santa Barbara, using mixed gas. He replaced nitrogen with helium. The bends comes from nitrogen in the blood.”

Another innovator was Phil Newton, who developed a new dive suit that was pretty expensive. “The Newt Suit was about the price of a high-end Porsche,” Rebuck says. Now, divers can reach depths of 1,000 feet.

“These technologies were developed by abalone divers over the years,” he says. “Abalone diving is no longer a fishery, but that technology lives on.”

And it hasn’t changed all that much with time. Rebuck says if you look at what the abalone divers were using and what’s in use today, “It’s essentially the same equipment.”

Rebuck’s book, which took eight months to compile and years to research, just came out at the end of July. It is currently available in San Luis Obispo at the Photo Shop store on Marsh Street and at Miner’s Hardware in Morro Bay, which has a rack with other Arcadia Publishing history books.

He hopes to get it into Coalesce Bookstore soon, as well.

Or readers can go online to Arcadia’s website and order the book (see: www.arcadiapublishing.com/products/9781467160285), which costs $23.99.