Terry Brown, left, and Jack Smith were both elected intot he Skateboarding Hall of Fame and Museum as part of the Hall Class of 2024. Brown was honored as a racer and Smith as an Icon of Skating. Photo by Neil Farrell

Two Morro Bay residents have etched their names into the history of Americana, after they were selected to the Hall of Fame.

Terry Brown and Jack Smith were among the 2024 inductees into the Skateboarding Hall of Fame and Museum, located in Simi Valley, Calif., and officially entered the world of living legends.

A Champion Racer

Brown was inducted for her pioneering career as a professional downhill and slalom racer in the 1970s and ‘80s. “I started skateboarding when I was 5-years old,” Brown recalls.

Smith said he started fooling around with skateboards in Los Osos, riding down a certain infamous street — Oakridge — in the “Summer of ‘74.”

“That’s when I started,” Brown laughs. It was on that gnarly hill where the two first met, too.

“We first met back in 1976,” Smith recalls. “We used to have races on Oakridge, which is off Los Osos Valley Road, back when there were no houses anywhere.”

“I remember you guys showed up,” he tells Brown, “and beat us all.”

She laughs and says “Back in the ‘70s skateboarding was a big deal.” She recalls races in Long Beach that drew crowds of 12,000 people.

She grew up in Santa Cruz skating and surfing. She used to thrash all over town on her skateboard until one day a professional skateboarder made her a tempting offer.

“I met this pro skateboarder and he asked me if I wanted to learn slalom?” Brown says. She was skating for the famous board shop, Santa Cruz Skateboards, and as she learned the ropes of slalom racing, she started working at the store.

“I used to ‘stuff wheels,’” she says, clarifying that stuffing wheels means packing the wheel bearings with grease. “We got Pendium wheels,” she says of her compensation, “and I got $4 a hour.”

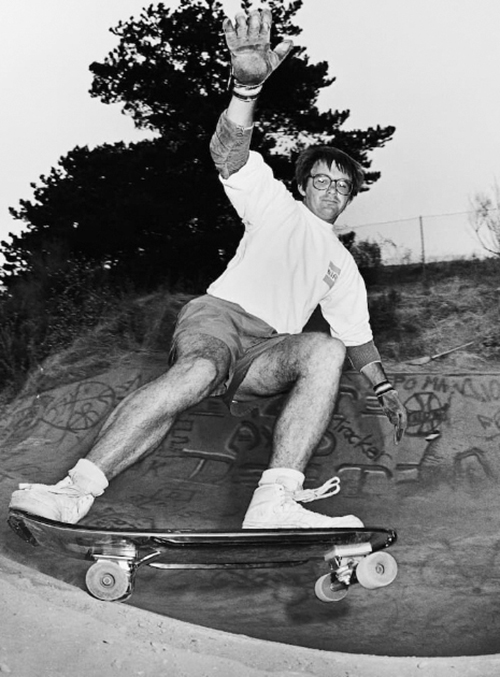

Jack Smith is captured skateboarding at The Ditch in Morro Bay back in the 1970s.

Smith laughs and notes that the minimum wage back then was closer to a buck-fifty an hour. Brown adds, “I got paid $5 an hour to test the wheels.”

Her rise to fame in skateboarding came quickly as she started winning races and world championships, too.

Photo shows Terry Brown at a skateboarding slalom competition from the 1970s.

Brown says she turned pro in 1976 and took Second Place in the Free Form at the Skating World Championships. “In ‘77,” she says, “I got First.” She competed in the slalom and giant slalom. She explains that skateboard slalom is just like skiing — a series of gates (or small traffic hazard cones), are laid out in a zig-zag pattern. With slalom, the cones are not very far apart, requiring a whole lot of hip swing to go back and forth quickly.

Giant slalom is the same thing but more spaced out and on steeper hills. The steepness makes a skater have to zig-zag, just to slow down.

Brown says her specialties were slalom and downhill, winning championships in 1977, ‘78, ‘80 and 2002. “I came back when I was in my 40s,” Brown laughs in response to a reporter’s puzzled look. That 2002 title came during one of the world championship events that Smith brought to Morro Bay, as the best slalom racers — young and old — converged here for street races.

How popular was skateboarding back in the good old days? Brown says that when she first started she was racing with the guys “and I always took fourth.” But, “I was beating the guys from Japan and Germany.” She recalls one particularly tough race course — “Derby Downs.”

Located in Akron, Ohio, Derby Downs is famous for being the home of the All-American Soap Box Derby for nearly a century.

The skateboarding course was laid out on the same hill the derby cars use. Smith says it’s a 900-foot downhill run that’s very fast.

“It was so slippery,” Brown says.

“Fast and slippery,” Smith adds. The course was downright scary; scary enough to have several of the competitors bow out.

It was the 1970s, and the liberation of the women’s rights movement spread to most of society, and skateboarding competitions for women would grow. Brown says there were usually nine or 10 entrants in the women’s divisions when she was racing. She won the downhill title in 1980 at races held in Capitola, next to her old stomping grounds in Santa Cruz. Brown says she raced at Capitola’s famous Begonia Festival in 1975-76 and ‘78-’80. Plus, “I was in the magazines a lot.”

Yes, it was perhaps her popularity in the various magazines that qualified her for the Hall of Fame. It certainly wasn’t for getting rich. Prize money back then was not much.

“The prize money was $10,000 for the guys,” she recalls, “and $1,000 for the women. That pissed me off.”

Brown is probably best known around here for the 25 years she owned Los Osos Fitness, the town’s only membership gym. She also coached swimming and water polo at Morro Bay High School for about 15 years. Her water polo coaching came from experience, as she played water polo while attending U.C. Berkeley in the 1980s, even though girls didn’t play water polo when she was in high school. She played her way onto the women’s Team U.S.A. B-Team, where she was the oldest player.

She passed on what she learned to her now-adult children — daughter, Keli Benko, and son Nik Benko. Keli won the Junior Women’s World Championships in 2003, her mom says, and son Nik was also a racer. She coached Nik when he was competing.

A Skating Icon

Morro Bay’s other Hall of Famer, Smith, was inducted as an “Icon of Skateboarding.”

Smith, Estero Bay News readers might recall, is a bit of an adventurer, famous for some pretty daring stunts, like riding a skateboard across the U.S. four different times including a groundbreaking first-ever crossing in 1976.

That was when Smith, and high school buddies, Jeff French and Mike Filben first hatched the idea. They’d all been skating down at “The Ditch” a concrete drainage ditch that runs between Quintana Road and Hwy 1. The trio came up with the idea, Smith explains, and he had a sponsorship with a skateboard equipment company in Florida and sent them a letter, seeking sponsorship for their adventure. They never thought they would go for it, he says, but they did, offering all the gear they’d need, a daily stipend and, “They said they would pay us $500 each if you make it.”

So they loaded up French’s 1969 Firebird for a support vehicle and devised a sort-of tag-team system, where one skater pushes the board down the road for a certain time, as the support vehicle moves ahead and waits.

The second skater took over from there, and so on. He said the plan was for each of them to skate 30-50 miles a day, and if they kept up that pace they’d cover 150-miles a day. “It took us 32 days,” Smith says, “going from Lebanon, Oregon, to Williamsburg, Virginia.”

It was the first time anyone had ever skateboarded across America, Smith says. The trek got quite a lot of publicity, enough that his skateboard from that trip is now in the Smithsonian Institutes’s collection, along with an electric skateboard he used to cross the U.S. for the fourth time in 2018. Brown also has a skateboard in the Smithsonian’s collection.

That 2018 journey, which Smith did alone, with his wife’s help in a support vehicle, marked the first time anyone crossed the U.S. on an electric skateboard.

He repeated the initial crossing in 1984, again with a group of local friends. “That was the first I had I’ve done for a cause — Multiple Sclerosis. That time it took 26 days.”

He of course wasn’t done with it by a long shot. “I waited 19 years to do the next one,” he says. He put together an expedition in 2003 to raise awareness of Lowe Syndrome, which his son had suffered with. “My son had died,” Smith recalls, “so we did another trip. That one was 21 days.” He attributes the shorter duration to “The equipment — the wheels and trucks — were so much better by that time.”

Following the death of his father in 2013, he decided to do it again. “My dad died of Alzheimer’s,” Smith says. “So I put together a 5-man team including my son Dylan, who was 21 at the time.” That trip took 23 days, he says. But his next crossing wouldn’t be so easy or short.

It was 2016 when he decided to try it again. “I always wanted to do it solo,” Smith says. By then skateboards with little electric motors had become the rage, so he decided to do the solo trip with those.

The plan was to leave from Eugene, Ore., but he didn’t get far before calling it quits. The expedition on the e-skateboard came to an end in Nampa, Ida. The age of distracted driving led to a few close calls as he rolled down the shoulder of the road. “I chickened out because of the traffic,” Smith says.

For the next two years, a little voice kept saying “Finish what you start,” some of the wisdom his late father taught him. So two years after chickening out, and after his wife retired, he decided to take up where he left off. “So I went back to Idaho with my wife driving the van. It took 53 days to finish.”

Smith isn’t just an icon for these history making treks across America, he too was a racer, competing for many years in slalom and downhill, and racing “skate cars” too. A skate car is a skateboard covered with a fiberglass shell, which much like a funny car body hides the dragster underneath.

It’s a skateboard in that it has wheels and trucks and steers by leaning to one side or the other, Smith explains. He was racing his skate car head first instead of feet first, laying on his stomach inside the contraption.

He was also recognized for the eight years he had the Morro Bay Skateboard Museum.

One More Time

Smith wasn’t done crossing the U.S., as he and a friend followed the old Lincoln Highway from Oregon to New Jersey in an electric vehicle, a converted VW van.

While not necessarily a feat of endurance, it could be considered a feat of ingenuity and planning, as first the VW was converted to electric drive, and then Smith had to plan places to stay overnight that could accommodate the VW’s need for a 50-amp circuit to recharge. But they got it done.

He now is off to cross the U.S. on an electric bike.

He plans to ride the Vintage E-bike across the U.S. solo, too, no support vehicle either. He plans to stay in motels this time instead of camping as they did before. “I don’t know how long it’s going to take,” Smith says. “It could take 30 to 35 days.” He says this time it’ll be easier because the bike uses a 110-volt plug in and not the 50 amps like the VW bus.

Smith will document his adventure on Facebook and Instagram.

Future of Skateboarding

Now that they’re officially part of skateboarding history, where is skating going in the future? Brown said skateboard parks are big and growing, with 4,000 in the U.S.

And slalom racing is going to be part of the World Roller Games in Rome, plus they do half pipes at the Olympics. The X Games has helped with the sport’s popularity too.

“Skating is now mainstream,” Smith says. “Some guys don’t like it; they think of themselves as rebels.”

That’s what skateboarders had to be back in the old days, as any empty swimming pool or as in Morro Bay, cement drainage ditch — in essence trespassing — would do for a skate spot.

The sport has gone in cycles, as back in the 1970s and ‘80s skate parks were privately owned. But skyrocketing liability insurance costs drove almost all of them out of business. In the 1990s, there were hardly any skate parks, anywhere, Smith says.

Then a group of people got the State Legislature to declare skating as a “hazardous activity” which meant a City could be protected from liability. Being recognized as inherently dangerous, was good because it meant cities could allow it, even build skate parks, and not get sued every time someone eats it.

“That’s why you see ‘No Skateboarding’ signs everywhere,” Brown says. Posting a town with warnings of the dangers of skating, protects the City. It of course does’t make skateboarding any safer, and Brown, who says she hated wearing helmets and knee pads, now strongly recommends any skaters today wear protective gear.

For more information about the Skateboarding Hall of Fame and Museum, see: skateboardinghalloffame.org.