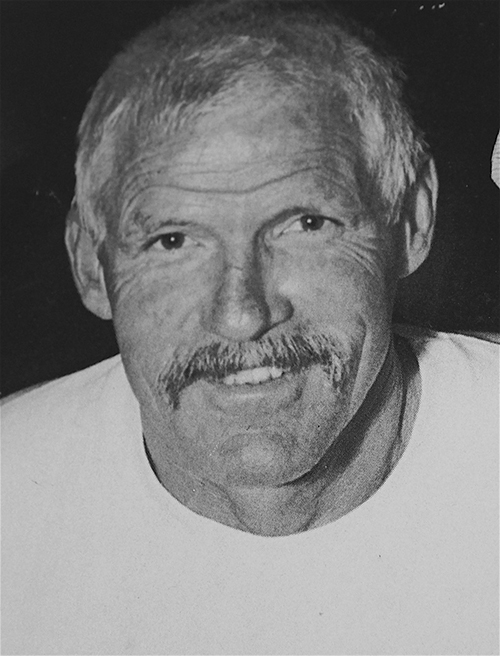

The news that retired Morro Bay Chief Harbor Patrol Officer, Dick Rodgers, had recently died came as a surprise for many Morro Bay residents, even those with roots sunk deeply into the community and the harbor where Rodgers was a legendary waterman and public servant.

This reporter, who somewhat morbidly but faithfully reads the obituaries in the local daily newspaper, had either missed the announcement of Rodgers’ passing, or he slipped away quietly, which is probably apt for a man who never sought the spotlight for himself.

The news came to this reporter from a City employee, Recreation Supervisor Kirk Carmichael. He and I had been chatting about a recent reunion celebration the City held for the Junior Lifeguards Program, which Carmichael said he and another retired Harbor Patrolman, Jim Kroll, began some 30-years ago.

Carmichael emailed the following notice, culled from the City Manager Scott Collins’ most recent newsletter and headlined, “Passing of a Morro Bay Legend.”

“Lastly and most importantly,” Collins, who came to Morro Bay just a few years ago and never worked with Rodgers, wrote, “we would like to remember and honor former Morro Bay Chief Harbor Patrol Officer Dick Rodgers, who recently passed away.

“Dick was a tremendous waterman, expert boat operator, intuitive emergency responder, and courageous leader. Before working for the City, Dick worked in the commercial boat-building industry in Morro Bay, in addition to tending hard-hat commercial abalone divers in the heyday of that industry.

“In the mid 1970s, Dick took a job with the City of Morro Bay back when the Harbor Patrol was a division of Public Works, both occupying the same small building that still houses the Harbor Department today.”

Collins makes note of the heroism displayed regularly by Rodgers, as well as all Harbor Patrol Officers, who come to the rescue of those in need of assistance — from swimmers and surfers that get caught in riptides, to boaters whose vessels break down at the harbor mouth.

“Dick worked during some of the most historical incidents the Harbor Patrol faced,” Collins wrote, “including the devastating 1988 South T-Pier Fire, and the 1983 capsizing of the San Mateo whale watching vessel by 20-foot breaking waves in the harbor entrance with 23 school children and nine adults aboard. All were successfully rescued due to the heroics of Dick, his fellow officers, and the Coast Guard.”

Among those on duty that day was former Harbor Patrol Officer Jerry Mendez. They were aided by numerous citizens at the little North Jetty Beach where they rushed the rescued victims, who waded into the water to help offload the school kids and the other victims.

In the end, the only fatality that day was the Captain of the San Mateo, who suffered a heart attack during what was to become known as “The San Mateo Incident,” which helped solidify the harbor bar’s reputation as among the most treacherous on the West Coast.

This reporter interviewed Rodgers in October 1993 for the fifth Anniversary of the 1988 South T-pier Fire, which killed two people and severely damaged the South T-pier, and burned some 13 boats that were tied to the pier that morning. It was an electrical short that sparked the most spectacular blaze in town history.

True to his humbleness, Rodgers said he got called in early that morning and remembered driving down Hwy 1 looking at a huge plume of black smoke rising high into the air, and thinking — to paraphrase — ‘What boat is big enough to cause a fire that huge?’

Dick Rodgers — along with Kroll — was the backbone of a harbor department that had service as its first priority and earned a reputation up and down the West Coast of being among the best, most helpful harbor patrols to the boating public. But for Rodgers, who apparently never took a vacation or a sick day, it all came to a stop in lightning fashion.

“In 1995,” Collins wrote, “Dick had a stroke and was unable to return to work, and for many years thereafter could be seen hiking across town to and from his North Morro Bay home with a backpack full of stones to rehabilitate himself physically.”

The Stroke left him partially paralyzed on half of his body and affected his speech. Soon after the stroke, he got a Doberman puppy and for years thereafter he was seen daily walking that dog on a leash all the way into town where he would help his late-wife Pat at her business, Gold Tree Jewelers. (As the dog grew up, people would joke that the dog was taking Dick for a walk.)

Long-time resident Nancy Bast, who used to have the Wash-n-Fold Laundromat on Dunes Street, sent Estero Bay News a memory of Rodgers. “What a shock it was to learn of Dick’s stroke, it just wasn’t fair that a human being of Dick’s worth, and seemingly healthy, should suffer such incapacitation!

“But he didn’t let the stroke keep him down — once back on his feet, he walked to town every day with his backpack on, determined to get his mobility back, always greeting people with a smile and good humor, practicing talking to people to re-train his speech.

“What we didn’t know is how determined to recover his strength and endurance he was by filling his backpack with rocks!”

Rodgers often stopped by the Laundromat to chat. “Often times on his rounds walking in town, he would stop by my Laundromat to haltingly ‘chat,’ never in embarrassment, always with humility.”

She added, “As far as Dick’s work in the harbor, it’s doubtful there will ever be anyone to match his care, humanity and management of the harbor.”

Soon-to-be retiring Harbor Director Eric Endersby, who worked under Rodgers as a reserve officer and ultimately became his replacement as Chief, said of his old boss, “Dick definitely came from the mold ‘When ships were made of wood and men were made of steel.’

“A true gentleman and courageous leader, Dick spoke more with his actions than his words, whether it was helping save 23 school children in the infamous San Mateo capsizing incident, leading his Harbor Patrol team by example and donning his trademark blue coveralls fixing a broken deck board, or hiking relentlessly back and forth across town after his stroke with a backpack full of stones to regain his strength.”

His skill piloting a boat was unmatched. “Dick was a tremendous waterman and boat operator,” Endersby said, “and involved in countless boat and surf rescues before the advent of GPS navigation and cell phones — when things often had to get done by intuition and the seat of your pants. If you were in trouble on the ocean, you wanted Dick on the other end of your radio.”

He was a man who made you happy to go to work. “I am very proud to have served under Dick Rodgers while I was a Reserve Harbor Patrol Officer,” Endersby said, “and forever humbled to have been chosen to replace him some 25-years ago.”

This reporter met Rodgers in 1992, when I became a reporter for The Sun Bulletin and charged with filling a section front of the newspaper with “waterfront news.”

But my favorite memory of Dick Rodgers wasn’t connected to the water at all. Around 1993 or ‘94, a trio of the Oakland Raiders came to town — including Hall of Fame player and then-coach Willie Brown — to play a charity softball game against the police department.

I was leaning against the backstop taking photos when Dick Rodgers came up to bat wearing a uniform of blue jeans and a white T-shirt with a big stogie cigar in his mouth. He took the cigar, tossed it onto the dirt near where I was standing and got into the batters box.

First pitch, he rips one between the outfielders that rolled to the fence. Dick flew around the bases like a man on fire, sliding into home plate in a huge cloud of dust — SAFE! — an inside-the-park home run.

As the crowd cheered, Dick got up, casually walked over and picked up the still lit stogie, stuck it back in his mouth and walked back to the dugout, as if he did that everyday.

The crowd went crazy, and if I recall correctly, I noted that incredible play in the story in the paper’s next issue.

I apologize that this tribute to a local legend doesn’t contain the normal obituary information about Dick, as I was unable to find any mention of his passing online and have lost touch with his son Larry.

Endersby summed up his service with the City: “Dick started with the City on Oct. 1, 1973, and became Chief Harbor Patrol Officer on July 8, 1986. He had a stroke in 1995, and used 2-years of sick and vacation time while recovering, but was never able to return to work. He separated from the City on disability retirement on June 10, 1997.”

He shares the sentiments of many. “Godspeed and rest in peace, Dick; your actions and exploits will go unmatched, and we will miss you.”